Pseudo-Science for the Snow Groomer

The Goal: Efficient Use of Manpower

Over the past several years, I have operated a winter recreation trail grooming program at a local nature preserve and park. Like many other environmental and recreational organizations, all the activities are conducted by volunteers, and finding a volunteer to groom trails on a cold winter morning is a challenge. In an effort to stretch our volunteer hours further, I decided to find an “efficient” way to groom trails by minimizing the time spent to achieve a satisfactory result.

The Criteria: User Satisfaction

After a new snowfall, the surface of an ungroomed trail is (ideally) covered with soft snow, oftentimes several inches deep. The recreational trail users in my part of the world marvel at the beauty of the new snow, and then after a few kilometers of skiing or snowshoeing, begin to complain that it is too challenging to walk or ski in deep snow. After many conversations with trail users, I unscientifically determined that the quality of their experience was related to the ease with which they could use the trails for whatever outdoor experience they wanted from their visit. The easier they could get around, the more satisfied they were. That’s why we started grooming, and that’s why we continue to do so. I then began an unscientific study of the relationship between user satisfaction and the only thing I have control over; the condition of the groomed trail surface.

The Answer: Snow Density

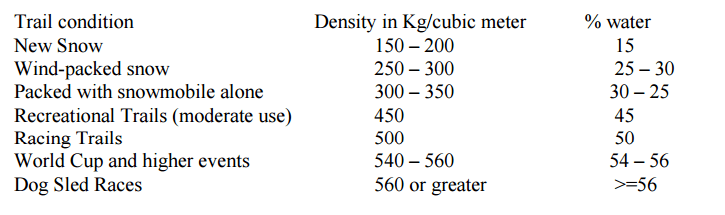

I began to find a link between the surface condition of a trail system and the satisfaction of the users. When trails were covered with new snow, they were often “too slow” for the average user. When they were very hard packed and icy they were “too fast.” When I could groom and set a track that looked like a Tidd Tech advertisement, all the users had a “great day for skiing.” I formulated that there exists a direct relationship between trail surface density and user satisfaction In terms of density, there is a “perfect surface” for each user or group of users. But do standards or guidelines for trail density exist? How could I easily measure them? What would I gain by doing so? How could I practically apply the results of this research? In my quest, I found a great deal of information about snow density on the internet, but little about how it relates to trail grooming. However, Cross Country Canada published a chart in their “Trail Grooming and Tracksetting” manual that offered the following guidelines for trail surface density.

Other web site and publications have suggested that beginners often like very low density surfaces because they want their falls cushioned and the slopes slow. Densities as low as 25 percent are suggested for “bunny slopes.” I reasoned that if I were to accept this chart as a guideline, densities of about 400 – 450 Kg/cubic meter would be appropriate to the abilities and the satisfaction of my audience of housewives, kids, weekend warriors, and occasional wannabe semi-pro skiers and snowshoers. A few at each end of the ability spectrum would be unhappy, but the vast majority would enjoy the winter recreation experience.

The Quest: Data Collection Methodology

How to achieve the mystical density number? For that we need to also look to the weather and the users for some information.

It is a widely known phenomenon that if snow just sits unmolested by trail groomers, it will get denser with the passage of time. Those thick layers of powder from early winter become harder with age and freeze-thaw cycles. The flakes eventually become cylinders of ice with much of the air gone, and the “welded” crystals will be denser than a recent snowfall, even if there is no other force of man or nature at work except the passage of time.

Of course, snowmobilers, skiers and snowshoers will compact the new snow into a more dense travel surface just by moving over it, and to a degree, the more use a trail gets, the firmer the surface will become. In fact, after 100 snowshoers jog over our trails during a competition, I worry about the surface being too firm and fast.

Of course, snowmobilers, skiers and snowshoers will compact the new snow into a more dense travel surface just by moving over it, and to a degree, the more use a trail gets, the firmer the surface will become. In fact, after 100 snowshoers jog over our trails during a competition, I worry about the surface being too firm and fast.

I therefore theorized that there are other forces working to change the density of trail surfaces as well as the mechanical groomer. Since time, weather, and repeated compression by users can dramatically change the density and structure of a trail surface, how do we know where we are on the density scale? We need to measure it.

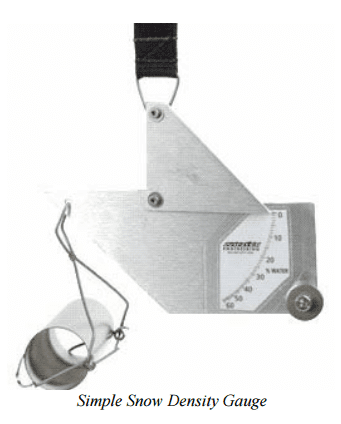

I mentioned earlier that there is quite a bit of information about snow density, but not a lot of information about the relationship of density to grooming. The reason is that much of that information is about avalanches, and snow density is one critical factor in determining the likelihood of an avalanche event. The equipment used to measure snow density for that purpose is quite suitable for surface density purposes. I selected a small snow density gauge consisting of a stainless steel tube and a gravity balance scale that allows me to read the percentage density directly off the scale without a lot of math. I simply push the tube into the snow more-orless parallel to the surface (not in the set track) and just under the surface until filled, then “cut off” the front and rear of the tube with a plastic card to even the snow with the tube ends without compaction, then hang the tube from the scale and take a reading as in the picture.

Survey Says: Results

I have taken these measurements when I groom over the last two winters. After a grooming session, I measure total snow depth on the trail, snow depth off the trail, snow temperature, air temperature, record any new snowfall since the last grooming, and snow density. I then record the accumulated information on a computer spreadsheet and look for correlations. Which bits of data seem to be related to each other?

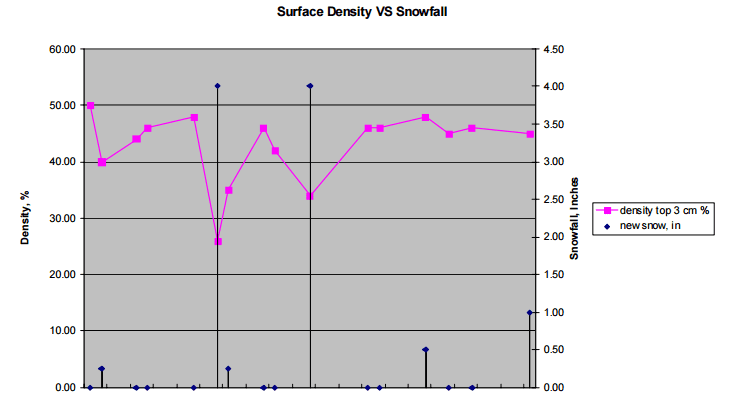

As we might expect, immediately after any significant snowfall the surface density of the trails will drop to somewhere around 25 to 35 percent. Don’t forget I have already rolled and groomed the new snow once before taking the measurements, so we should not expect the 15 to 20 percent “new snow” density from the chart above. After repeated grooming sessions the density has climbed steadily until it reaches more than 45 percent.

Since my “target audience” seems to like a density of about 40 percent, I will groom until I am about there, and then stop until upcoming event preparation, wear-and-tear or new snow deposits requires me to groom again or reset a track.

Unfortunately there is no “rule of thumb” about grooming frequency as it relates to density. In my experience it usually takes three or four groomings of several inches of fresh powder to get to 40 percent density. But if the temperatures stay very cold and the traffic is light, then more grooming will be required. If there are multiple freeze-thaw cycles, only an inch or two of new snow, or lots of trail traffic, it is possible that only two groomings will get to the 40 percent density. I have found that it is best to do the actual Simple Snow Density Gauge measurement of density by scale and sample rather than to try and formulate a ”rule of thumb” or system of rules to predict the density of the trail. Trying to come up with a simple equation to predict the interaction of snowfall amounts, the passage of time, user compaction, weather, and grooming activity has proven difficult. It’s simple, quick, and reliable to just get out the scale when I’m on the trail and do a density check. It’s become part of my daypack contents that always go with me when I groom, along with the sunglasses, foot warmers, and ear plugs.

Conclusions: What’s the Point?

I believe I have devised a simple system that allows a groomer to produce a uniform and satisfactory experience for the winter recreational trail user based on the measurement of the snow density of the trail surface. This will not only produce a more consistent experience for the user, but will also allow for volunteer groups to determine when further grooming would be non-productive or even counter-productive.

There is room for improvement. Over time I am beginning to get a sense of what 40 percent density snow feels like under my boots. If there was a “snowball” test that could reasonably accurately and consistently determine snow density based on the ability of a handmade snowball to retain its shape, or some similar test, it would dramatically improve our ability as groomers to produce the desired result. However, I don’t think there is an accurate, simple test at this time that can differentiate between “slightly too soft” and “just right.” I’ll probably have to stick with my scale and tube method.

In the meantime the winter recreation trails have made winter visits to the preserve more frequent than summer visits, and I view this outcome as the most positive indicator of a successful program. Recently I tested a Tidd-Tech Gen II at a demo day, and I’ve concluded that I could probably shave some more time off my volunteer hours if I have a wider, more capable groomer than my current four foot Tenderizer.